Behaviour Stories: A Guide To Removing Organizational Waste.

By Ahmad Fahmy

“If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.”

— Loren Eiseley

Fish tanks are living pieces of art. They mesmerize adults and children with their colors, movement, and majesty. But behind the beauty is endless hours spent managing the tank. The success of the fish tank depends on your ability to control the one thing you can’t see: the water. The water dictates whether the sensitive Orange Spotted Filefish will thrive in your tank, or die within days.

It is all about the water.

Culture, like water to a fish, is invisible and generally goes unnoticed. Yet it's the most important factor for everything and everyone in it.

Culture, not money, is the reason that organizations can’t retain certain talent.

Culture is the reason organizations don't take risks.

Culture is the collective behaviors of organizations, both good and bad.

It’s all about the culture.

Behaviour stories helps you manage the culture.

Introduction

I help companies stop maladaptive (toxic) behaviours and adopt adaptive behaviours. In other words, I help them manage their culture.

I define culture as the codified behaviours of organizations, both adaptive (good) and maladaptive (bad). The bad behaviours are usually born during periods of stress and are the result of quick fixes, and local optimizations. Systemically removing these bad behaviours is necessary for creating the environment that unlocks people's greatest asset; their ability to collectively solve difficult problems in elegant ways, or in other words, to create beauty. That is the supposed role of most change/transformation coaches and management gurus. To intuitively usually spot a “smell” and suggest a solution. Except it is not that simple.

Jerry Weinberg, in his popular book, the Laws of Consultancy states that a client will tell you what the problem is in the first 5 minutes. I have not found this to be the case. The client will tell you a problem, but they will not tell you the problem. Or in some cases, the client will tell me what to do. “I have a problem with X and I need you to do Y.” “We have a problem with requirements, can you help fix our requirements problem.” Experientially, I’m certain they don’t have a requirements problem, they probably have a communication or trust problem.

In most cases, I do not know what the problem is let alone what the solution should be. But one thing I know for certain: there are always toxic behaviours. I need to uncover them, understand where they came from, and suggest solutions to stop them. Doing so will take time, but there is nothing more important for an organization than to manage the culture.

Behaviour Stories is a process to help leaders manage the culture. Specifically, it's a process that surfaces bad behaviors, and systemically and sustainability eliminates them. It is not lost on me that the acronym for the process is B.S. That is by design. While I hope that the process itself is not BS, Behaviour Stories are inherently bad. They are either the stories we tell ourselves as to why we cannot do something, or the starting point for the actual cause stopping us from achieving the goals of the organization. Behaviour stories are the cultural debt. The cultural underbelly.

I have not invented anything new here. Based on established patterns, theories, and techniques, I have simply combined them in a way that has worked for me and my clients and has proven to be repeatable. Everything I recommend below; I have tried myself several times.

Continuous Improvement or Flip The Organization?

Do organizations need to fundamentally change their structure in order to impact culture? Does culture follow structure as many believe?

This link between structure and culture is supported by the works of MIT professor Edgar Schein and Harvard professor John Kotter, both of which posit that culture and structure are tightly linked. This idea is also supported by anecdotal stories of IBM’s radical restructuring in the 90s by Lou Gerstner, Jobs’ restructuring of Apple, Microsoft’s restructuring under Satya Nadella, and later Twitter’s Elon Musk. All these radical restructurings resulted in changes in culture.

They all have one thing in common - they faced an existential crisis and have leaders that can weather the storm when the organizational system fights back.

Toyota has popularized the idea of continuous improvement or Kai Zen. Amazon has also created a practice of marginal gains at its distribution centers.

The context in which continuous improvement makes sense over radical changes:

A stable environment

A culture that supports learning

Risk-averse cultures

Environments where there is strong resistance to radical change

Behaviour stories works well in these contexts.

BS Principles

The following are my guiding principles for organizational behaviour change. These principles are a confluence of theory, observation, and practical experience. The six principles represent my current mental model of changing organizational behaviour for most organizations.

The behaviour stories process actualizes these principles. The process is meant to be modified, overloaded, or even completely discarded and changed depending on one’s context and situation. An understanding of the principles that underpin and inform the process will help you modify and improve it.

1. Manufacture PURPOSE & URGENCY

“An object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force.”

— Newton's First Law of Motion

Behaviour change usually requires external force. This is true for both the laws of physics and for changing singular or organizational human behaviour - it is both axiomatic and supported by research. Dr. Kurt Lewin asserts that an organization must first be “unfrozen” before a new norm is established. Peter Senge, author of one of the seminal works on system thinking asserts that an organizational system is optimized not to change, and that change requires external force or pressure. Kotter’s model’s first step to organizational change is to create urgency and purpose.

There are two types of forces that create urgency and purpose; uncontrolled and manufactured. Uncontrolled forces as those that are out of the control of the department or the company; market downturns, currency crises, and internal software failure. These are events that are not planned or manufactured but force the organization to react. Most companies are usually equipped to deal with these events. These events usually amplify the best and worst parts of the culture.

However, it falls on the shoulders of leadership to utilize a manufactured sense of urgency and purpose. It never ceases to amaze me how rarely this is done right. The primary tool still utilized to create purpose and urgency is the carrot and stick - fear of loss of the job or position or promotion coupled with the promise of some sort of remuneration. That is because the alternative is difficult - creating a genuine drive. Dan Pink’s Drive equation is simple yet useful here; to create drive in an organization, people need three things: Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose. Roughly translated, management need to hire great people, give them purpose, and leave them alone.

Rather than constantly reacting to stress and responding to an extrinsic force, manufacture the same necessary force on your terms. 3-5 years is simply too long of a time horizon. 3-6 months makes the objective far more real provided it is doable and not a stretch objective.

The key is to ensure that the organization does not resort to toxic behaviours to deliver.

2. Do EXPERIMENTS (not Projects)

"Failing is one of the greatest arts in the world. One fails toward success."

— Charles Kettering

The idea of failure seems more popular than ever these days. It has reached cliché status. Kent Beck, founder of Extreme Programming and a thought leader in the software industry tells a story of something that happened while he worked at Facebook. An engineer made a mistake that cost Facebook $21M. What happened as a result? Nothing. The engineer’s management referred to the error as a $21M learning opportunity. Their rationale was that if engineers are afraid, they will not take risks. If they do not take risks, they will not innovate, and if they do not innovate then.

Juxtaposed to the Facebook response, I was once working with a major bank that had built a cutting-edge cloud platform designed to radically reduce operation and maintenance costs by millions while allowing for rapid prototyping. Hundreds of millions of dollars were invested. Yet, few internal organizations would use it. As I investigated, the root cause pointed to a fear of failure or making mistakes, and that management and developers were too risk-averse to migrate to the new platform. In fact, the control gates put in place institutionalized fear. These control gates were born out of need and a real-world scenario - an event in the history of the organization that resulted in a senior leader probably saying, “I need assurance that this will never happen again!”

In my experience, most mature organizations, optimized to maintain their position, will not behave like Facebook. Failure will be painful and most times will be punished. No one likes or wants to fail. The cost is usually too high because the bets are too big. The solution lies in experimenting within a quick feedback cycle - trying something in short intervals, failing, recording observations, and moving on. The organization does not have to contend with sunk cost fallacy. For example, “Let’s try something for the next month. If it doesn’t work, we will try something different” Vs. “We are going to invest 400 million dollars over the next 5 years to build Y” all the while praying Y works out. The major difference is the cost of failure. Losing a month of time and resources but gaining learning and experience can be considered a net gain. Losing 5 years of opportunity cost and 400 million dollars cannot.

3. Manage FRICTION by removing and creating it

“Continuous Improvement is not about the things you do well – that’s work. Continuous Improvement is about removing the things that get in the way of your work. The headaches, the things that slow you down, that’s what Continuous Improvement is all about.”

— Bruce Hamilton

I first heard of this idea from a friend of mine when we were discussing diet and training. During one of our conversations, I asked him what his secret to success was. “Friction” was his response. “I remove friction from the behaviours I want, and I create friction in those I don’t want.”

To remove friction, he prepares all his fitness clothing and checks his equipment the week before, schedules all his training in his Outlook calendar, and marks it as ‘out of office’. The idea is to remove as much friction as possible from his desired behaviour, which is not to miss a training session. Diet is where he creates friction. He loves food, but the behaviour he wishes to create friction in is eating foods that are not good for him. So he removes all the junk food from his house. There is friction created between him and a tub of Ben and Jerries.

It may seem like a lot of work and overhead. There is overhead and setup work, but the reward is that it helps overcome decision fatigue and is a small price to pay to achieve your desired behaviour change. What are 2-3 hours on Sunday to enable positive new behaviours and stop toxic behaviours? It takes a little bit of upfront discipline to help enable a week of discipline when you just don’t feel like it.

His laws of friction can be summarized as follows:

Determine what behaviours you are trying to start and stop

Make it as easy as possible to establish the desired behaviours

Make it as difficult as possible to stop toxic behaviours

A little bit of upfront discipline pays dividends

As luck would have it, I have worked with Graeme on a few occasions transforming his organizations. The question we had was how to apply laws of friction to his organization. An organization’s transformation at its basic level is stopping toxic bad behaviours and starting positive behaviours. After determining what behaviours we wanted to stop and start, we created friction in three ways:

Created constraints

Measured, visualized, and socialized the constraints

Removed friction and supported new behaviours through:

Training

Tooling

Management support

Communication

Coaching

4. Small NEAR-TERM WINS that snowball into MASSIVE WINS

“Stretch goals can be terribly demotivating. When stretch goals seem overwhelming and unattainable, they sap employees’ intrinsic motivation. The enormity of the problem causes people to freeze up, and the extrinsic motivator of money crowds out the intrinsic motivators of learning and growth.”

— Daniel Markovitz

Almost all organizations I work with are engaged in some large program to deliver some transformational project that is almost always delivering in 3 years and costs 10s of millions if not 100s of millions of dollars. In my experience, almost all of these efforts lead to failure and demoralized staff. According to the 2015 CHAOS Report, only 29% of all projects were successfully completed on time and budget.

I prefer the idea of small near-term (3-6 month) deliveries that deliver value and built momentum. In software products that translates to frequent deliveries to the customer.

The idea that small, near-term wins can be more effective in motivating people and driving progress is supported by various studies and theories in psychology and organizational science. This concept is often associated with the idea of "quick wins" or "small wins", suggesting that achieving immediate, visible results can build momentum, boost morale, and foster further engagement. According to this theory proposed by Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, setting specific and challenging goals leads to higher performance than easy or vague goals. Moreover, when these goals are broken down into smaller, manageable tasks (small wins), individuals are more likely to achieve them, providing consistent motivation and a sense of achievement.

Albert Bandura's self-efficacy theory posits that an individual's belief in their ability to succeed in specific situations affects their motivation and behavior. Small wins can boost self-efficacy, as they provide evidence of one's competence. Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer, in their book "The Progress Principle," present their research showing that the single most powerful motivator at work is the sense of making progress in meaningful work. Even small progress can increase an individual's engagement, productivity, creativity, and happiness.

The nature of the task, individual preferences, and workplace culture can also influence the effectiveness of small wins. For some people and in certain contexts, long-term, bigger goals may be more motivating. It's important to consider a balanced approach, leveraging the power of both small, near-term wins and long-term goals based on the specific circumstances.

5. Change VERY LITTLE but change the RIGHT BEHAVIOUR

"Sudden and overwhelming change can trigger fundamental survival instincts. Effective leaders recognize this and move quickly to help followers regain a sense of balance and equilibrium."

— Gary Bradt

Stable systems, by default, do not want to change. "They did too much too fast," "we needed evolution not revolution," "they didn't understand our culture" are statements I have heard numerous times. A key question I have had in my work related to change of any sort is how much change to introduce. I have studied this question and even looked to political science for questions. The best answer I can come up with is it depends on the following factors:

The urgency for change, intrinsic or extrinsic

The ability of leadership to absorb the blowback of the change from the system

Research indicates that introducing too many changes at once can be counterproductive. Established models by the likes of John Kotter and Kurt Lewin support an incremental change process to prevent overwhelming employees. Moreover, studies highlight that excessive simultaneous changes can lead to change fatigue, resistance, and reduced change capacity. Thus, strategic and gradual implementation is crucial in effective change management.

Various studies and theories suggest that trying to change too many behaviors at once during an organizational change initiative may be less effective or even counterproductive. This is related to the concepts of change fatigue, resistance to change, and the capacity to absorb change. Here are a few key studies and concepts:

John Kotter's 8-Step Change Model emphasizes the importance of implementing change in a stepwise manner to prevent overwhelming employees. Kotter argues that trying to change too much at once can lead to resistance and confusion.

Kurt Lewin's model, one of the cornerstone models of change management, argues for a gradual process of "unfreezing" old behaviors, "changing" to new behaviors, and then "refreezing" those new behaviors into place. This gradual process can help ensure change is manageable and sustainable.

Organizational change can often lead to change fatigue, which occurs when employees are asked to follow through on too many changes at once. A study published in the Journal of Organizational Change Management in 2010 found that change fatigue can lead to reduced change capacity and cynicism about change efforts. Neuroscience research also supports the idea that trying to change too many behaviors at once can be overwhelming. The brain prefers routine and certainty, and too much change can create stress and resistance. This concept in organizational theory, coined by Cohen and Levinthal, refers to a firm's ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends. Too many changes at once can overwhelm an organization's absorptive capacity, making change initiatives less effective.

The key question is then which behaviours should an organization target?

6. Actively MANAGE the CULTURE

“You have to manage a system. The system doesn’t manage itself.”

— W. Edwards Deming

How often do top executives worry about culture in their organization? Stock price, profit, and loss will take center stage in their headspace. Culture is usually relegated to something HR would worry about. I believe that managing the culture of the organization is the principal responsibility of top executives, everything else follows from there.

Lou Gerstner, the former CEO of IBM, said, "Until I came to IBM, I probably would have told you that culture was just one among several important elements in any organization's makeup and success — along with vision, strategy, marketing, financials, and the like... I came to see, in my time at IBM, that culture isn't just one aspect of the game, it is the game."

Frances Frei and Anne Morriss, in their book "Uncommon Service," said, "Culture guides discretionary behavior and it picks up where the employee handbook leaves off. Culture tells us how to respond to an unprecedented service request. It tells us whether to risk telling our bosses about our new ideas, and whether to surface or hide problems. Employees make hundreds of decisions on their own every day, and culture is our guide. Culture tells us what to do when the CEO isn’t in the room, which is of course most of the time."

There is a substantial body of research that suggests leaders play a crucial role in actively managing and influencing organizational culture. Leadership styles, behavior, and communication can shape the values, norms, and behaviors that constitute an organization's culture.

Edgar Schein, a well-known researcher in the field of organizational culture, proposed a model suggesting that leaders are the primary architects of organizational culture. Leaders initiate and manage culture by establishing and communicating the values, beliefs, and assumptions that shape the organization's practices and behaviors.

The Competing Values Framework: Developed by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983), this framework outlines four types of organizational cultures (clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchy), each associated with different leadership styles. Leaders, according to this model, influence their organization's culture by embodying and promoting the behaviors and values associated with their leadership style.

1. CAN GOALS Create Urgency & Purpose

“A higher rate of urgency does not imply ever-present panic, anxiety, or fear. It means a state in which complacency is virtually absent.”

— John P. Kotter

Toxic behaviours usually emerge in times of organizational stress. As those behaviours become acceptable, they become habitual and eventually part of the culture. The first thing you need to do to surface these behaviours is to manufacture a sense of urgency. However, you need to do this by creating a goal, rather than reacting to a problem.

This goal needs to have three particular attributes to manufacture the right environment for improvement:

It must be Constrained.

Constraints are what drive behaviour change. A normal organizational goal usually involves doing something faster, better, or cheaper. Unconstrained, the organization will try to deliver that goal using the same behaviour patterns. Constraints explicitly specify what cannot be sacrificed to meet the goal. There is no use in achieving the goal by doing more of the same.

It must be Achievable.

These are just above the current ability of the organization and create the positive momentum and confidence to continue growing. The people building the product will determine this.

It must be Near-term.

Having the goal 3-6 months away makes the goal more real and increases the level of urgency.

Further criteria can be employed to enhance the goal, for example, a fourth attribute could be stipulated such as; this goal must provide immediate customer value.

A CAN goal provides just enough external force to start the behaviour change process. Without a compelling reason, genuine change is unlikely, and you are more likely to engage in change-theater. All companies and individuals experience outside forces that force some sort of change and the idea here is that the organization manufactures this force. Dr. Kotter's change model starts with Create Urgency and that is exactly what a CAN goal does.

Compare the following statements:

“I need to lose weight!” / “We need to be more efficient!”

Vs.

“I have a beach vacation in 4 months with a bunch of friends and their families. I really need to lose 5 pounds!”

2. Identify Organizational Waste with BEHAVIOUR STORIES

“The most dangerous kind of waste is the waste we do not recognize.”

— Shigeo Shingo (Toyota)

Behaviour stories (BS) are waste. You need to identify them, understand why they exist, and remove them, or else they risk preventing you from achieving your CAN goal. The template is simple:

To achieve the [CAN goal], [X role/person/group] has to stop doing [Y behaviour]

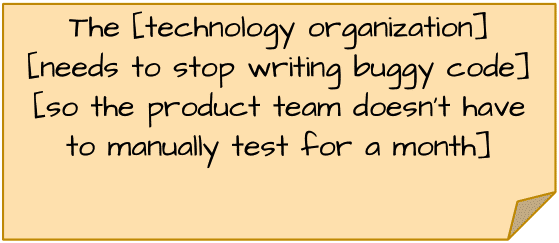

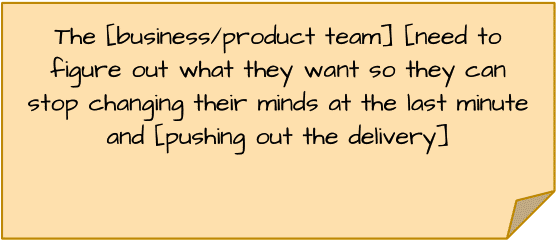

Examples:

The Process:

1. Gather BS.

Think of as many behaviour stories as you can. Gathering BS is a collective journey. One or two people may have answers to what needs to change. Write these on Post-it notes.

2. Visualize Cultural Debt.

Cluster these post-it notes on a wall once you have gathered a substantial amount. The clustered behaviour stories will provide an accurate representation of the organization’s current actual culture.

Use a wisdom of crowds technique to vote on which behaviour stories are the biggest blockers to achieving the goal within the constraints.

The resulting list of toxic behaviours is in many ways the cultural underbelly of the organization or department. I assure you they will be different from the words excited in some hard material on the walls of the building. This is what the “cultural debt” looks like. Aka "Cultural Underbelly", “Waste”, “Organization debt”, “Bad behaviours”, “The fat”.

You now have a prioritized list of the behaviours you are looking to change. BS is limited to stopping activities: You are looking for waste and trying to avoid solutioning. By limiting what behaviours need to stop rather than start, you expedite the path to wasteful activities and avoid solutioning. While this can degenerate into a “finger pointing” exercise, it has a cathartic effect that can then result in a meaningful discussion.

The gathered BS are often a narrow perspective of a generally larger, more complicated story. What people think is the problem is usually a symptom of a problem that originates elsewhere. These stories are imperfect, incomplete, and are merely a smell that points you in the right direction. That is why they are called behaviour stories. They are BS. Solving the symptom is like taking painkillers. It only masks the problem and gives short-term relief while letting the root problem fester. You need to understand the root cause of these behaviours to dig them out.

3. Root-Cause Analysis.

Use the lens of the CAN goal to help you isolate the real waste: To achieve the [CAN goal], [X role/person/group] has to stop doing [Y behaviour]. Apply root cause analysis techniques such as 5-whys to get a deeper insight into why those behaviours occur.

Each behaviour story would have evolved into a more complete story with both the symptom and potential root causes. You now have a CAN goal and a number of clear behaviour stories that you feel are stopping you from meeting the goal. Consider what you may have done in the past. You would adopt frameworks without really understanding what behaviours you were trying to change. Now you understand what behaviours we are trying to change and why they exist.

3. BEHAVIOUR MAPPING: Generating ORGANIZATIONAL EXPERIMENTS

“Successful problem solving requires finding the right solution to the right problem. We fail more often because we solve the wrong problem than because we get the wrong solution to the right problem.”

— Russell L. Ackoff

This is the final step in the process. Equipped with a deeper insight into the behaviour stories preventing you from achieving your CAN goal, you now need to generate as many experiments as you can that target changing the underlying behavior of the story. Remember, you are solving for the root cause, not the symptom itself.

Naturally, some of these experiments will make management nervous. However, they do not need to last longer than one month and can be evaluated for effectiveness at that point. This draws the process to a close with a renewed sense of urgency and a number of experiments that would be tried during the next few months.

One month later, hold a review meeting to evaluate the experiment selected, the status of the goal, and the status of the constraints. In the case that it is a success, you can make it implementable in the long term. If it is unsuccessful, try the next experiment on your list over the next month and repeat the process.

BS Process

The process is incredibly simple and designed to eventually become second nature.

Conclusion

Behavior stories is nothing more than an attempt to help people actively manage their culture. It does not create a massive revolution. Rather, it establishes a sustainable momentum that can be built on by creating an environment that allows change. It is a humble attempt to help organizations systemically remove their BS and create environments where people love to work and where elegant products and services can be built that provide value to customers.