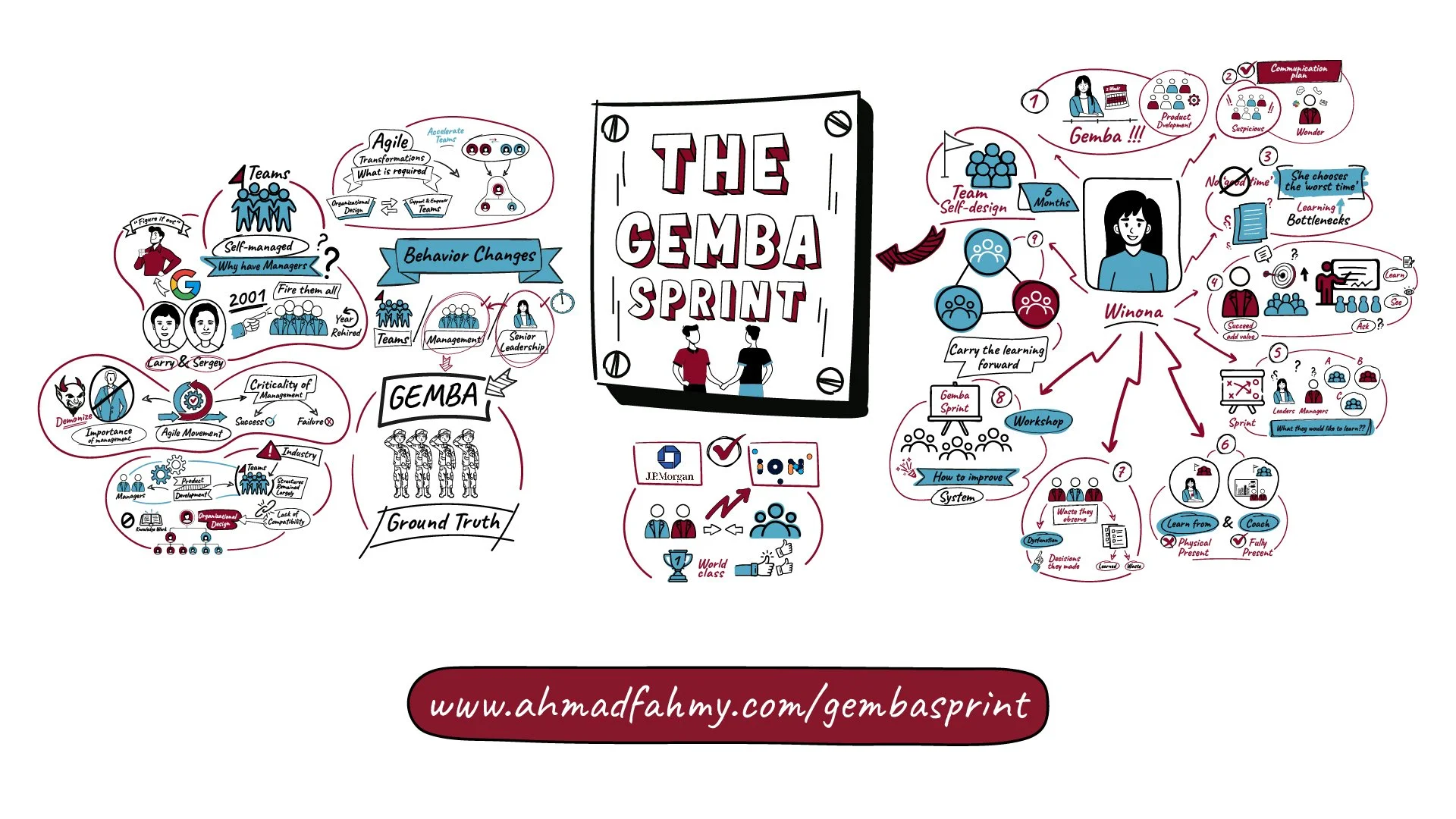

Go, See & Do: A Guide to Running a Gemba Sprint.

By Ahmad Fahmy

Introduction

If teams are self-managing, why do you need managers?

This was the question that Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin debated in 2001. Ultimately, they decided that that management was unnecessary and initiated what they called a Disorg and fired all managers.

A year later, there was an intellectual battle between them and their coach Bill Campbell regarding the value of managers until they finally agreed that they should just go ask the Engineers themselves. To their surprise, the Engineers wanted managers to return.

“These engineers liked being managed, as long as their manager was someone from whom they could learn something and someone who helped make decisions.”

A year later management was returned.

The global agile movement has been effective at making the concept of self-managing teams ubiquitous, in a sense creating systemic industry-wide “Disorg”. The difference is that the majority of managers remain in management purgatory.

Like the experiment at Google, managers are required, but not the traditional command and control manager. Managers with a different set of behaviors are required:

• Managers who teach

• Managers who coach

• Managers who make things go faster by removing waste

The challenge facing us as an industry is how we reframe the manager role to create the necessary environment for managers to unlearn toxic behaviors and adopt useful behaviors.

The Gemba sprint is an experiment designed to create such an environment and reverse the polarity between leadership, management, and teams.

From walking to sprinting

"Go see, ask why, show respect" -Toyota Chairman Fujio Cho

Key Differences Between Gemba Walk, MWBA, and Gemba Sprint

The Gemba walk was popularized in the mid-to-late ’90s by the Toyota Product System [2]. The Gemba walk is a 6-step process to observe the reality of what is going on. A manager focuses on a specific process step and seeks to understand what the reality is by employing open-ended questions to learn the reality of the process.

Management By Walking Around (MBWA) is a management approach that encourages physically visiting the “actual place” regularly. Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, constantly visited his stores and expected his managers to do the same [3]. Despite running a multi-billion-dollar company, Howard Schultz, the CEO of Starbucks, makes it a point to visit 25 stores in order to “witness the customer experience personally. [4]”

MBWA and Gemba walks have visiting the “real place” in common. Gemba walks, however, go further to add a more specific purpose and a set of steps to discover the reality.

These differences led W. Edwards Deming to say about Management By Walking Around:

“Management by walking around’ is hardly ever effective. The reason is that someone in management, walking around in a non-structured way, has little idea about what questions to ask, and usually does not pause long enough at any spot to get the right answer.”

Like the Gemba walk, the Gemba Sprint has specific goals and a process to achieve them. The Gemba Sprint, however, transcends the Gemba Walk in that it also includes organizational goals.

Gemba Sprint Goals

The goals of the Gemba Sprint can be divided into three: Organizational, Process, & Anti-goals [5].

Managers see what is really happening

“Farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you're a thousand miles from the cornfield.” - Dwight D Eisenhower

Management by the status update is a reality of scaling to a large complex organization. Perfectly aligned boxes and unified fonts of a PowerPoint presentation can easily hide the realities of the ground. The real world is far more nuanced and complicated and lost when presented in a deck. In the words of retired four-star general Jim Mattis, “PowerPoint makes us stupid. [6]”

If you can create a PowerPoint representation of a shanty town, while useful for some purposes, obscures the reality on the ground. Nothing can give a genuine appreciation of the reality of the shanty town more than taking a walk through it.

Learning & Teaching

“Learning organizations are organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together."

- Peter Senge

A primary objective of the Gemba Sprint is bidirectional education. Participants in the Gemba Sprint are expected to both learn and teach. Managers, by definition, have a better understanding of navigating the organizational system to get “things” done. Managers should take the Gemba Sprint as an opportunity to teach the system to the teams. Organizational leaders understand where the organization is going and can implant purpose and urgency into a team. The teams are the most aware of what is happening on the “ground”.

Managers teach and do not solve

“There are three kinds of leaders. Those that tell you what to do. Those that allow you to do what you want. And Lean leaders that come down to the work and help you figure it out.” -John Shook

Most managers are generally very busy. Between people issues, product issues, & corporate issues, most calendars are so full that they need to schedule lunch.

When they are not on calls or in meetings, managers are usually solving problems. I often work with managers that have a steady stream of people walking into and out of their offices seeking help to get unstuck or untangled. This results in two issues: managers become a bottleneck & the quick fixes can often have dangerous consequences.

Quick fixes can be dangerous because they are often implemented as a result of incorrect systems thinking and incomplete information. As stated in the Weinberg-Brooks’ Law: More software projects have gone awry from management’s taking action based on incorrect system models than for all other causes combined.

Managers should seek to overcome what Senge calls learning disabilities through the discipline of systems thinking and going to Gemba. The combined disciplines of learning to see through systems thinking and going to the place where value is created result in a manager with organizational superpowers. They can see what most can't, hear what most are too busy to hear, and grasp what few can: reality. Like not missing lunch, it all starts by prioritizing it in the calendar.

An organizational system is far more intricate and complicated than a mechanical system due to the non-deterministic nature of people. Those who understand the organizational system are often called "good politicians" or "political". While this loaded term is usually used to deride someone, I believe it’s a useful and necessary skill for success.

Managers make the mistake of spending too much time understanding and navigating the system. While the Gemba Sprint seeks to get the manager closer to Gemba, managers should also explain to the team’s member system dynamics so they themselves can avoid local optimization thinking.

Once developing the skills of seeing, managers should teach teams to solve problems rather than solve them themselves. This will make the organization go faster by removing this blocker, but also free up the manager to consider higher-order issues.

The Product Owner brings teams closer to the customer and teams bring the Product Owner closer to the code

Product management and Product Owners advocate on behalf of the paying customer or internal users of the system. Technology management, however, is usually involved when there are problems or issues or when they need to provide high-level estimates. This disintermediation results in the team's loss of purpose and urgency. Purpose, as Daniel Pink postulates, is a necessary ingredient for intrinsic motivation or drive as he calls it. Without drive, management is forced to use extrinsic motivation which can stifle innovation.

Product Owners at Gemba should embed purpose into the teams. It’s also important that the teams bring the product owner/management closer to the code by showing them the technical debt that resulted from short-term thinking mistakes, local optimizations, and time pressures imposed by management.

I recall the following conversation between the product owner and one feature team during a Gemba Sprint in India.

"Why do you have to make the simple change in many places?'' asked one product owner to his teams in India.

"Remember that customer feature you said we had to get in by that date?" A member of the team replied.

"The only way we could actually do that was to create a copy of the code",

"Why would you do something like that?" The product owner was asking a perfectly valid question.

"Given the time constraints we had, we were worried about creating regression issues, we didn’t want to take the chance of impacting other customers.”

"You should have told me," He said. “This is a nightmare.”

"We never spoke to you directly back then, our managers did."

Increase empathy

“Empathy begins with understanding life from another person's perspective. Nobody has an objective experience of reality. It's all through our own individual prisms.”

- Sterling K. Brown

By visiting Gemba and working with the teams, leadership, management, coaches and Product owners gain a greater sense of empathy for what the teams must deal with (e.g. context switching, slow build servers, environments, changing requirements).

Managers have a lot they must deal with: fire drills from above, getting yelled at by customers and internal clients, personnel issues, and unending meetings. Product owners must deal with angry customers and business and commercial expectations. Scrum Masters focus most of their time on protecting their teams from all of the distractions that can result from all of the above.

Going to Gemba affords a great opportunity for management, the Scrum Master, and Product Owner to understand what it feels like to be a member of the team and allows them to connect with them in a better way.

During a Gemba Sprint in India, a CTO was asking the teams why the build was taking so long, they said that the build server was antiquated and that their request for a new server was declined by infrastructure.

"What do you do while the system is building?"

"We go get some Chai."

A new server was ordered as well as dual monitors for every developer. The deeper insight that the CTO gained was the offshore development center was part of a cost-reduction strategy. So the local lead was very sensitive to cost, hence one monitor.

What they will invariably see is that teams are trying to do the right thing, it is a system that has been created that makes doing a good job more difficult.

The empathy that is gained from this experience pays dividends.

In one case, the CIO of the organization was working with his team on an Oracle upgrade. It was time for lunch.

"Let's go have lunch," remarked the CIO.

"Your lunch is being prepared in the boardroom; we believe," replied the teams.

"Where do you eat lunch?"

"The canteen."

"Then that is where I will eat."

The CIO of the parent company sat in the canteen with developers in an offshore development center and shared their lunch eating with hands although he is unaccustomed to doing so.

Human moments such as the above empathy bring the organization together in immeasurable ways.

The Gemba Sprint experiment

Software product development is inherently complex, and its complexity is further multiplied by each organization’s particulars and nuances. As such, the Gemba experiment is a list of suggested things to try and avoid [8] so that you can design the Gemba Sprint that is right for your organization.

Before the Gemba Sprint

Asking managers to join a team is sometimes met with a lot of resistance from both managers and teams. There is an invisible wall of mistrust, fear & insecurity between management and those with “hands-on keyboards” that makes the traditional Gemba walk seemingly uncomfortable for both parties. This exercise is meant to create an environment for this type of activity but also leverage fear and uncertainty to get people to learn new things and think in new ways. Whether or not manufacturing this type of experiment is a good or bad thing can be a matter of debate. I find leaving management “as is” while the teams "evolve" through the agile organization is unfair to all parties.

1. Find someone to own the idea

Find a volunteer who will own this idea rather than rent it.

The idea of owning an idea is that someone takes an idea and makes it their own. I am a runner and for many years I would not shut up about running. It was an idea that I passionately owned. A rented idea is that which you do not own but are borrowing for a purpose such as my wife is telling me I am not allowed to eat meat on Monday.

The Gemba Sprint is a difficult experiment to run and you want someone who genuinely believes in it, who will own the Gemba Sprint, modify it, rename it, and make it their own. External coaches can advise, help and guide, but someone from within the organization should own this experiment. With one client I worked with, the Gemba Sprint was renamed Unicorn Sprint because they did not like the word Gemba. That was a great sign.

2. Over-communicate

What can make or break this experience is communication. It is very easy for this type of experiment to be misunderstood or misconstrued. Decades of behaviors as a result of theory X assumptions can create deep-rooted mistrust between management and "workers." You can't really solve that immediately, but you can soften the effects through lots of effective communication.

a) With everyone

Preparing everyone for the Gemba Sprint by explaining the “whys” of the exercise will reduce resistance and encourage participation. Start with an introduction in a town hall or other type of session where the senior leader explains the Gemba Sprint and how the exercise is tied to an organizational goal. The leader should also open the forum up for feedback as well.

Recap the session with various forms of written communication or information radiators such as emails, newsletters, posters, and other physical artifacts that can remind people of when the Gemba Sprint is and what their roles are in the Sprint.

b) With management

One-on-ones should be scheduled with everyone who is taking part in this exercise to explain what their roles are, and what is expected of them. This provides an opportunity for everyone to offer suggestions, ask questions and express their concerns. Senior organization leadership should be in these meetings to reinforce the idea of job safety but not role safety.

Examples of common concerns to be addressed during communications:

The scrum masters

"What if things go better without us running the Sprints"

Product Owner

"I don't have time for this"

"I'm not a developer"

Management

"We are too busy..."

"The time is not right"

Teams

"This will disrupt us"

"What if we work much harder during the Sprint, will we be expected to work just as hard after the Sprint?"

"What if I say something that will be used against me in the future"

“I’m a tester, not a coder”

Senior Leadership

“This seems very expensive”

“We already know what is going on”

3. Choose the worst time to maximize learning

There is no perfect time to do a Gemba Sprint. Rather than trying to find the “perfect” or “slow” week if such a week exists, find an imperfect week. Before or directly after a production release is a great option and a great time to maximize learning.

4. Break the system

In order to accelerate the learning and highlight bottlenecks, you can consider stress testing the system to maximize learning. This can be done by attempting to complete the same amount of work in a condensed time frame.

The idea behind this is to performance test the system to both expose the bottlenecks as well as maximize the learning, not an attempt to cram more work into a shorter time frame. The key difference in the shorter Sprint is that management and product teams are present in the "doing".

Other “break the system” activities could be releasing on demand, developers testing instead of coding, or challenging an archaic process or status quo...whatever the activity, be sure to communicate, communicate, and communicate the intent so that it is not misunderstood.

5. Learn how to learn at Gemba

“Learning is not compulsory... neither is survival.” – W. Edwards Deming

The time leading up to the Gemba Sprint is a good opportunity for all involved to take classes and workshops to learn how to be an effective leader, communicator, coach, and teacher and learn some technical skills.

6. Learn the 5 whys and other root-cause analysis patterns

The purpose of 5-whys is to discover and solve the underlying issues that cause a problem. 5-whys employs “counter-measures” rather than simple solutions. A countermeasure ensures that the problem does not arise again rather than just eliminating the symptoms.

7. Learn how to ask good questions

“If you do not know how to ask the right question, you discover nothing.”

- W. Edwards Deming

Learning to ask good questions is a learnable skill. Here are some concepts and methods:

Consider learning about cognitive biases and mental models to help you realize that your whole view of what is happening is incorrect at worst and incomplete at best.

Consider learning about the differences between dialogue and discussion to help you actively suspend your mental models to enable you to understand the system.

Consider learning how to system model with the teams to visualize the complexity of the organizational system. “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” – H. L. Mencken

Consider learning Humble Inquiry: the art of asking authentic questions to a person to learn their perspective.

Try Clean Language as a template to ask better questions.

8. Learn how to read code

I’m not suggesting you learn to write code, I’m suggesting that you learn to read. There is a big difference between learning to write great poetry and reading poetry.

9. Develop an eye for waste

“When you go out into the workplace, you should be looking for things that you can do for your people there. You’ve got no business in the workplace if you’re just there to be there. You’ve got to be looking for changes you can make for the benefit of the people who are working there.”

- Taiichi Ohno

Lean defines waste as any activity that does not add value to the paying customer. Therefore any activities that impede value creation are waste. When looking at the entire lead-time (the time the customer asks for something until it is delivered to them), highly observative and effective managers can uncover tremendous amounts of waste while some managers can also be the cause of generating waste and doing harm at Gemba.

The default is that many managers try to coerce teams to go faster when in reality they can make the system move faster or increase the flow of value by removing waste. A manager should ask not what the team can do for them, they should ask what waste they can remove from the system.

During the Gemba Sprint

1. Start with an all-hands breakfast and level-setting

Kick off the day with an all-hands breakfast. Food is important and overall a nice gesture and eating together relaxes people.

During the all-hands, leadership should re-emphasize the reasons behind the Sprint as well as the rules of the Gemba. For example:

a) Repeat the goals of the Gemba Sprint

b) Repeat what the Gemba Sprint is and is not

c) Repeat the rules:

i) Only observed blockers should be collected. Teams and managers should refrain from putting their pet peeves on the list

ii) Managers should refrain from doing their day job while at Gemba.

iii) Every day ends at 5 pm to lessen the observer effect.

d) Agree on the format of the waste observations. For example:

i) Document only observed wasteful items and activities experienced or witnessed, not existing “pet peeves” or other impediments.

ii) Observe and document how many hours this wastes during the Sprint.

iii) Use the Behavior Stories template (optional):

In order to meet the goal X process/ person/group Must stop Y behavior. Create a simple way to measure the size of the waste.

2. Joining teams

Joining teams can happen before the Gemba Sprint or during Sprint planning.

Those who are joining teams should be free to join any team they wish for any reason they wish, but once they join, they must stay for the remainder of the Gemba Sprint and be committed to meeting the team’s Sprint objectives.

3. Create a “Gemba” checklist for managers

"Employees don’t quit their jobs, they quit their managers."

a) Things to do at Gemba

Start a list of Tech Debt – prioritize it using business terms

Don’t fix everything as it happens

Watch for a recurring pattern and commit to fixing one thing

Have lunch with the teams

Lighten the mood / elevate the tone

Talk about why the work is important to the client

Make personal notes about the feedback you would like to share when the timing is right

Look at the Sprint plan – is the team adjusting? accounting for risks?

If team dynamics are ‘off’; observe! Try to find out the causes and conditions driving the individual behavior(s). What about the whole is impacting the one?

Lead a Product Backlog Refinement session

b) Things not to do at Gemba

Don’t worry about looking dumb

Don’t worry about trying to impress the team

Don’t rush to judgment or solutioning

Leave for long periods of time

Get frustrated at the first sign of issues/problems

Constantly check phone or email

Check-out

c) Questions to ask the team or team member

How are you doing?

How can I serve you better?

Can I pair with you?

Is it worth communicating this to the product owner?

Would you mind explaining "x" to me

Tell me more about why you do “x” this way?

How is this tested?

Can that be automated?

Can this step be done earlier in the process?

How will this impact quality?

Should this be documented for others?

How will this impact the customer?

Has this item met the definition of done?

Does the process of delivering vary for some PBIs (there? If so, why?)

Has this item met the definition of Done?

What’s on your mind?

d) Questions to ask me

Is this an antiquated process that I can remove?

Is there a teachable moment here?

Can I make their job more enjoyable?

Is this a value-added activity?

Is this a blocker I should remove or a blocker I should teach the team to remove?

Is this dysfunction related to a historic management decision?

How is the team interacting with the greater organization?

Is this a teachable moment for the rest of the team?

What skills should I learn in the future to make me more effective at Gemba?

Is there a workplace-there workplace suffering that I could reduce or eliminate?

What can I do to increase my credibility?

What can I do to increase my reliability?

What can I do to increase my intimacy with the team?

What can I do to reduce my self-centeredness?

4. Coding at Gemba

It’s not necessary that managers/leaders/product owners/Scrum Masters do engineering work, although it’s possible. Some of those people were former developers in a past life and while their coding skills may be rusty, the idea is that they pair with as many of their team members as possible to maximize the learning and develop an eye for waste. Everyone should be empowered to help do work where possible.

Consider mob programming (or other methods)

Mob programming is a technique that has been around for a long time but has gained some popularity in recent years. The basic idea is that a team of individuals work on a single problem together, at the same time. This is a good experiment to try for two reasons:

1. Mob programming exposes a lot to the new team member in a compressed period of time.

2. Mob programming can also illustrate that their intuition is not always correct, that a team of people working on a problem is not a waste of resources, but it can be a force multiplier.

Think of some other methods that will push teams beyond their comfort zone to try something new.

5. Hold a daily retrospective

Memory is imperfect and the rush to get work in the last days of the Sprint may eclipse much of the important learning. Have a daily “light-weight” retrospective instead of waiting until the last day of the Sprint.

It should be fun and well-facilitated!

Three important reasons for the daily retro:

1. Signals at the end of the day and a stoppage of work. This is to ensure that teams do not put in extra hours due to the phenomenon called the “observer effect” which states that the mere observation and measurement of activity will alter its results.

2. Discuss the day’s data and any missing observations.

a) Take this opportunity to prioritize the list of waste

3. A chance to reflect on the day. How did today go and how can we improve tomorrow?

After the Gemba Sprint

1. Radiate information

Within a couple of days of the end of the Gemba Sprint, the output of the Gemba Sprint should be communicated.

Be sure to include the waste collected, waste removed, and any new experiments or items that will be attempted.

Create and keep the central “waste management board” alive with what has been removed and what material impact has been measured or observed. Theoretically, the more waste is removed, the more value the customer should receive.

2. Retrospect on the Gemba Sprint

Reflect on the Gemba Sprint itself. Schedule a lunch away from the office and retrospect on how the Gemba could be improved the next time. Ask the manager, coach, or Scrum Master to keep a list of “do’s”, “don’t” and “keep doing”.

3. Have a Waste Management Workshop

After the retrospective on the Gemba, the teams should return to the centralized waste board to discuss the observations of the Gemba and what actions to take to address them.

4. Conduct an anonymous survey

The intention of the survey or other feedback form is to gather what was unsaid. There may be pressure to declare the Gemba Sprint a success and those with constructive criticism may feel the need to be silenced. The objective is to gather constructive criticism while minimizing toxicity.

Some potential questions:

Should we do this again?

How would you improve the next Gemba Sprint?

What did you find valuable about this experiment?

What did you learn from this experiment?

5. Celebrate!

“The prevailing system of management has crushed fun out of the workplace”.

- W. Edwards Deming

Congratulations on finishing your Gemba Sprint. Don’t forget to celebrate this significant milestone on the path to continuous improvement! Conducting a Gemba experiment can push people beyond their comfort zone which always deserves a celebration.

Final Thought

Like any experiment, a single Gemba sprint will not solve all your issues. It is meant to be a huge first step in a long journey of repairing years of management antipatterns and creating a new set of behaviors. Eventually, every sprint should be a Gemba sprint:

Where teams spend the majority of their time producing value for the customer

Where managers help the teams deliver faster by removing waste rather than “pushing” them

Where managers coach and teach

Where product owners and organizational leaders provide vision and understand what is happening at Gemba by going to Gemba

Where empathy and compassion are prevailing values

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the people that reviewed this and provided valuable feedback:

Bas Vodde, Michael James, Victor Grgic, Tim Born, Gene Gendal, Deb Wren

References

[1] An anti-pattern is a common response to a recurring problem that is usually ineffective and risks being highly counterproductive. – Wikipedia

[2] https://www.creativesafetysupply.com/qa/gemba/what-is-the-origin-of-gemba

[3] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/management-by-walking-around

[4] https://us.experteer.com/magazine/management-by-wandering-around/

[5] https://osboncapital.com/what-are-anti-goals/

[6] https://theweek.com/articles/673091/general-mattis-save-military-ban-powerpoint